by BBT

Right-wing

fundamentalists often claim that the United States is a “Christian

country,” some even going so far as to argue that it should be

governed by “Biblical Law.” I'd like to take you

back in time to look at the theocratic government that existed in

northeastern Massachusetts in the 1600s and the terrible consequences

of its theocratic excesses; these influenced the founders of the

United States to reject theocracy in favor of separation of church

and state.

Let's

start with a brief recollection that, by the 17th Century

in Europe, there were already many examples of why the fusion of

religion and political power was, often literally, a double-edged

sword – nice for those wielding the power, but not so good for

those on the wrong side of the religious-political divide. They were

often persecuted, stripped of their power and property, and exiled or

executed. The power balance often shifted rather quickly, too, as the

“ins” became “outs.” No one was immune, least of all royalty.

English King Charles I, who had incurred the suspicion of the

Puritans who controlled Parliament when he married a Catholic, and

whose tumultuous reign included many military misadventures, led

England to civil war and was beheaded in 1649. His Catholic

grandmother, Mary, Queen of Scots, had met the same fate in 1587

during Elizabeth I's reign.

Death of Mary, Queen of Scots

This

turmoil in England took place during the first century of English

colonization of North America. At the same time, England was battling

for control of Ireland, Scotland and Wales and engaged in struggles

for European supremacy as other countries (especially Spain and

France and to a lesser extent Portugal, Holland and Germany) were

also colonizing the Americas. Almost all of these political struggles

had religious and economic overtones or underpinnings.

The

disputes were far more complex than “Catholics vs. Protestants.”

Not only Catholics, but Quakers, Lutherans, Mennonites, French

Huguenots and other Christian groups were persecuted in England,

Holland, Germany, France and elsewhere; where they had political

power, they persecuted others. Jews were often marginalized in Europe

and America. Religious affiliations were very complicated and very

political. More on this here. While differences about religious dogma could be significant, it was

the fusion of religion with political and economic power that often

led to war and conflict.

There

was also a real belief in witches who actively partnered with the

devil to harm to people, crops and livestock. Witch-craft explained natural disasters, and “witches” - most of whom were women - were

often scapegoated during plagues, droughts, crop failures etc. From

the late middle ages to the late 17th Century, an

estimated 80,000-100,000 Europeans were executed for witch-craft.

Many more were accused.

"Witches" burned at the stake

Against

this backdrop, religious persecution was probably the rule more than

the exception if you were not one of the “ins” at any particular

point in time. For these, and many other social, economic, political

and other reasons, many people chose to take the dangerous voyage to

an unknown land.

From

the outset, there were distinctions among the colonies, and within

them, about religion. New York and Pennsylvania attracted Mennonites,

Lutherans, Quakers, Jews and others who were persecuted in Europe. In

Massachusetts, the Pilgrims who settled the Plymouth Colony were

“Separatists” who did not follow the Church of England, unlike the Puritans of the

Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded a decade later. The Puritans' religious “platform” was to “purify” the Church of

England with rigid interpretations of biblical tenets.

The

Massachusetts Bay Company was rigidly Puritan, but even so, it

rejected the call by some adherents for government strictly based on

Biblical law. Instead, Massachusetts colonial law expanded upon

English law and incorporated theocratic admonitions. The Body of Liberties was the

basis of the first Massachusetts code of laws.

The

Body of Liberties is in many ways a remarkably progressive document

for its time, enumerating the rights of colonial “freemen” and even including some rights for women, children, servants, “strangers and

foreigners” and even animals. Slavery was ostensibly abolished,

except that the exceptions in effect legalized slavery in most

instances. (Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1780.) In all, these

laws, as they applied to civil matters, were remarkably progressive

for the 17th Century.

They

were not progressive as they applied to religious beliefs, however.

Missing church on Sunday was a significant offense that could result

in imprisonment, whippings and fines. If you were convicted of being

a witch, or a blasphemer, or an adulterer, or a believer in anything

other than what the Puritans believed, that was a capital crime for

which the punishment was being put to death.

Quaker

Mary Dyer being led to her execution

And

they did. Quakers, a new religious group in the 1650s, were persecuted and hung in Massachusetts because they refused to adhere to Puritan orthodoxy. They disrupted church

services, engaged in civil disobedience, defied bans and persistently

challenged the Puritans' rules. Even on the gallows, they steadfastly

refused to save themselves by betraying their beliefs. Here is an

account of the persecution of Quakers in Massachusetts, which ended

when King Charles II intervened on their behalf. (Yes, by then, the English were more tolerant than the Puritans.)

There

was dissent against the Puritans' rigid theocracy from the earliest

days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Roger Williams, a brilliant

and charismatic minister who arrived in Massachusetts in 1631, was a

separatist who rejected Puritan orthodoxy and preached tolerance. He

was a strong and passionate advocate of freedom of religion and the

separation of church and state, and is said to have strongly

influenced Thomas Jefferson and other founders on this issue. He was

offered the ministry in Boston when he first arrived from England,

but declined because he refused to adhere to their strict tenets,

arguing among other things that there should be no punishments for

blasphemy, heresy, adultery or other religious transgressions. He

became the minister in Salem, where he was generally well-respected,

although his “radical” ideas continued to attract attention. In

1635, the Massachusetts General Court convicted him of sedition and

heresy, ordering him to be banished. He narrowly avoided being

jailed, escaping on foot during a blizzard and walking 105 miles in

deep snow to Narragansett Bay, where he was taken in by Native

Americans. He went on to found Providence Plantation, where laws only

applied to “civil things,” not religion – the first “western”

government with separation of church and state. The area attracted

many Quakers, Baptists, Jews, and others who were persecuted elsewhere, and was

the most tolerant and progressive of the colonies – so much so that

Connecticut, Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colonies tried to get

it abolished. Williams went to England and succeeded in getting a

charter for the area that eventually became Rhode Island.

Roger Williams and Narragansetts

Anne

Hutchinson was another charismatic religious leader. She led

well-attended weekly meetings of women in Boston that professed a

“covenant of grace” that differed from Puritan orthodoxy. Her

gatherings became so popular that she had to expand them to include

men, including then-Governor Henry Vane. The Puritans became

increasingly alarmed at her “free grace” views and growing

influence, which were at the root of the Antimonian Controversy. The Puritans

voted Vane and others supporting “free grace” out of office in

1637 and prosecuted Hutchinson later that year. She was convicted of

contempt and sedition and banished; she escaped to Providence

Plantation, establishing a settlement nearby. These settlements, with other religious dissidents,

united and formed the colony and later the state of Rhode Island,

which became a bastion of religious tolerance. The colony passed laws

outlawing witchcraft trials, imprisonment for debt, most capital

punishment; Rhode Island also outlawed slavery in 1652.

The

Puritans were not only concerned with ridding Massachusetts of

religious dissenters; they soon turned their attention to

witch-craft. From 1648-1663, 80 people were

accused and 13 women and 2 men were executed. The first was Margaret Jones, a midwife and healer whose 1648 execution was witnessed by then-12-yearold John Hale, who later played a key role in the witch-hunts of 1692. In 1688, Cotton Mather, the influential minister of the Old North Church, zealously persecuted a laundress known as “Goody

Glover” for bewitching the Goodwin children; he witnessed her

execution, took in her children and wrote a book Memorable

Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions.

This book quickly

became a “best seller” in Massachusetts. Perhaps as a result, in

1689 there were enough accusations of witch-craft that the jail in

Salem could not hold all those accused.

This

all came to a boil in 1692,

the year of the infamous Salem Witch Trials. The witch hunt began

not in the city of Salem but in Salem Village (now the town of

Danvers; see map here); soon it spread

to communities throughout northeastern Massachusetts. This account suggests that unrest due to King William's War and other socio-economic factors played

a role.

The

trouble began in January 1692 when two girls in the household of

Reverend Parris started having “fits” and behaving strangely –

much like the Goodwin children as described in Mather's book. (It's

surprising that the girls themselves weren't accused of being

witches; some say that is because they were so young that they were

presumed innocent, yet a four-year old child was accused.) Soon, other girls started showing similar

behavior. (Interestingly, no boys were affected.) A doctor could find

no physical ailments and concluded witch-craft was the cause of their

afflictions.

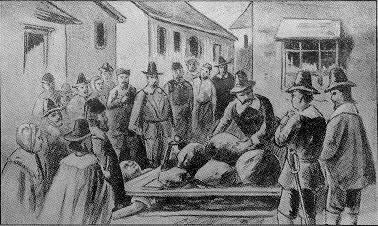

Salem Witch Trial

This

led to the accusations. The first accused were women who attracted attention because they were outspoken, not submissive, provocative,

“unpuritan,” or social outcasts.

Sarah

Good and Sarah Osborne were accused in late February, along with

Tituba, the Parris family's slave. Tituba

confessed to being a witch and was spared; her confession was

instrumental in causing the hysteria to expand, but she later

recanted it. Sarah Good, who had been born to a prosperous family but lost her property in a

legal battle, by 1692 was a pregnant beggar and outcast who was an easy

target; she was hung in July and her infant daughter was born and died

in the jail. Good's

4-year old daughter was also accused and imprisoned. Sarah Osborne may

have been targeted because she hadn't attended church due to illness. She was an in-law of the Putnams and had been involved in disputes with them. She

was never tried; she died in jail in Boston after being held captive

for several months. Bridget Bishop was another woman who did not fit

the mold of women in Puritan society; she was a tavern keeper, had

been married 3 times, was described by some as promiscuous, and

had been twice accused of witch-craft previously. She was the first

of the accused to be tried because the magistrates felt that it

would be easy to convict her because of the prior accusations. They

were right; she was the first to be hung, in June of 1692.

While

those accused at the outset of the witch hunt were all “outcasts”

in some fashion – they did not conform to the Puritan model –

this soon changed. That spring and summer, Martha Corey and Rebecca

Nurse and many other well-respected members of the communities were

accused, and some, including Corey and Nurse, were convicted and hung that summer.

Martha Corey was known for her piety and regularly attended church; however, she did not believe in witch-craft and was outspoken about her opinion that the girls making the accusations were lying. At that point, they accused her. She had no doubt that she would be exonerated; however, the girls' actions at Corey's trial gave the impression that they were possessed and controlled by Corey, leading to her conviction. She was hung in September.

Rebecca Nurse was an elderly, pious, well-respected resident of Salem Village. She

was accused by Anne Putnam and her daughter, among others, although

Putnam's brother-in-law and others in the family were among those who

spoke in Nurse's defense. Apparently Nurse had criticized the younger

Anne Putnam for bad behavior on several occasions. Another accusation

came from neighbor Sarah Holten, who claimed that Nurse cast a spell

that caused her husband to die, after they had argued because his

pigs destroyed Nurse's garden. 39 people risked

their own lives by signing a petition attesting to her good character and seeking her release. She was initially acquitted, but the

girls accusing her starting having fits in the courtroom after the

verdict was read, and Chief Magistrate Stoughton ordered the jury to

reconsider. Nurse was then convicted and hung in July. To the end,

she proclaimed her innocence:

“I

can say before my Eternal Father I am innocent and God will clear my

innocency…The Lord knows I have not hurt them. I am an innocent

person.”

Rebecca Nurse's sisters, Mary

Easty and Sarah Cloyce, were also accused, and Mary was executed.

Sarah was released from prison in January 1693.

Rebecca

Nurse Homestead

Remarkably, part of Nurse's

300-acre 17th Century farm and her house are still intact

in the midst of a very suburban area; the property includes a graveyard with her

remains (dug up from Gallows Hill and moved by her grandson) and

those of several other victims of the 1692 witch trials. Three Sovereigns for Sarah was filmed there. (The Salem Village Historic District is well worth

a visit; however, I was alarmed to see that several key buildings in

other parts of Danvers, including the Israel Putnam house and Sarah Osborne's

house, are falling into disrepair.)

Elizabeth Howe was a cousin of Rebecca Nurse. Howe's husband was blind, leaving

her with the tasks of running the farm as well as the household. She

had an “assertive personality” and had been accused of causing

fits in a girl ten years earlier. In 1692, she was accused of

afflicting cows, horses and pigs. At her trial, she said: “If

it was the last moment I was to live, God knows I am innocent of any

thing of this nature”.

She was hung. Here is an excellent account of Howe's story.

Martha Carrier's “crime

was not witchcraft but an independence of mind and an unsubmissive

character.” Susannah Martin apparently ruffled feathers by contesting her father's will. Anne Pudeator was a nurse and midwife who was accused after some of those

in her care died or babies were stillborn. Wilmot

Redd was an “eccentric” character with a volatile temper who was

known to get into lively arguments with her neighbors in Marblehead.

Margaret Scott of Rowley was an elderly beggar. "Non-conformist" Sarah Wildes, Mary and Alice Parker were also executed.

John

Proctor was the first man accused (along with his wife, Elizabeth). Proctor was a prosperous farmer with large landholdings in the

southern part of Salem Village, in what is now the city of Peabody.

He is one of the main characters in Arthur Miller's play, The

Crucible (which is not

historically accurate). He was executed and his wife was also

condemned, but her execution was delayed because she was pregnant,

and she was released the following year.

Harvard

graduate George Burroughs, who had been a minister in Salem Village,

was hung the same day as Proctor, even though he had no “witches

marks” on his body and was able to recite the Lord's Prayer, which

Puritans believed that witches could not do. After he spoke, the

crowd was so moved that they began calling for him to be freed, but Reverend Cotton Mather stepped in and argued that he and four others should be executed.

80-year

old Giles Corey, whose wife Martha was accused, was tortured and

crushed to death because he refused to enter a plea, thus preventing

the court from seizing his property from his heirs.

John Willard was accused after he refused to arrest those whom he thought were innocent; he was hung. Samuel Wardell, his wife and step-daughter were all accused. He confessed to

witch-craft to save himself, but then recanted, and was hung. George Jacobs, Sr. was also executed, based on testimony by his granddaughter, who was also accused and was trying to save herself.

Convictions

were often based on hearsay and “spectral evidence.” This was

testimony based on visions and dreams that the accusers – many of

whom were children - claimed to have, with no tangible proof. Spectral evidence did

not meet the legal standard even then, but the magistrates allowed it

anyway. The trials led to the execution of 20 people; at least 5

others died in prison. Another 150 people were jailed in horrible conditions that year, and

200 more were accused. By the fall, more leaders were speaking out against the trials and particularly against spectral evidence.

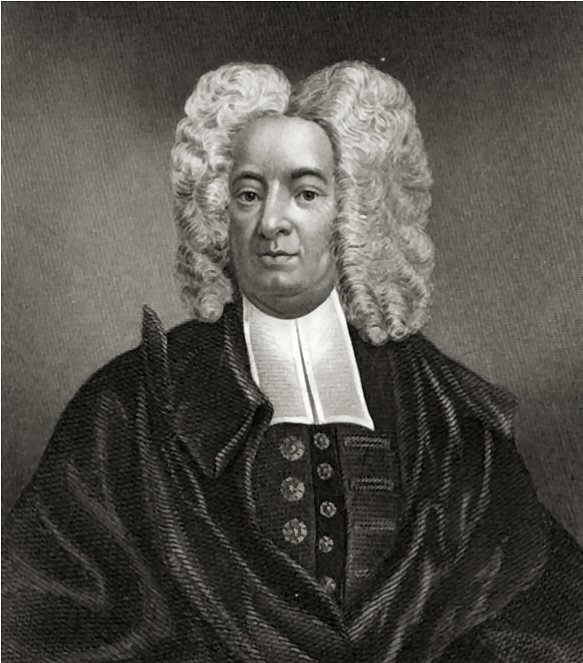

Cotton

Mather

Several

Puritan ministers like Cotton Mather played a key role in instigating

the witch-craft hysteria; others helped bring it to an end. Reverend Samuel Parris, minister of Salem Village, helped inflame the hysteria that began in

his own household. Reverend John Hale of Beverly testified against

the accused in several cases, but his views changed dramatically when

his wife and several parishioners were accused. He became a critic of

the proceedings and two years later wrote a forthright account,

admitting that they had lost their way and became irrational out of

fear. Reverend Dane in Andover, where many accusations took place,

argued against the hysteria and especially against the use of

spectral evidence, and is considered one of the heroes who helped

save people from death. Samuel Willard played a similar role in Salem

Village and helped foster reconciliation after the end of the

hysteria.

Ipswich town records indicate that ministers there spoke out against

the witch-craft accusations in 1689 and again in 1692.

Even Cotton

Mather wrote a letter in early June condemning the use of spectral

evidence. His father Increase Mather (who was the influential

president of Harvard College) decried the use of spectral evidence in

a letter in early October, writing: "It

were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one

innocent person be condemned."

Thomas Brattle and Robert Calef were community leaders in

Boston who were highly critical of the witch trials and whose

critiques helped bring them to an end. Calef was a particular critic

of Cotton Mather, blaming him for establishing fertile ground for the

hysteria to occur. His book More Wonders of the Invisible World is

a direct rebuttal of Cotton Mather's 1693 book Wonders of the

Invisible World; Calef's book is

one of the best contemporaneous reports on the witch trials.

Eventually,

the accusers went too far, accusing more and more respected members

of the community, including the wives of Hale and other ministers,

and even the wife of Governor Phips. In the fall he disallowed

spectral evidence and disbanded the special court; early the next

year he put an end to the trials, and in May he pardoned and released

the remaining prisoners.

“And

now Nineteen persons having been hang'd, and one prest

to death,

and Eight more condemned, in all Twenty and Eight, of which above a

third part were Members of some of the Churches of N. England, and

more than half of them of a good Conversation in general, and not one

clear'd; about Fifty having confest themselves to be Witches, of

which not one Executed; above an Hundred and Fifty in Prison, and Two

Hundred more accused; the Special Commision of Oyer and Terminer

comes to a period. -- Robert

Calef

Governor

Phips wrote:

“When

I put an end to the Court there ware at least fifty persons in

prision in great misery by reason of the extream cold and their

poverty, most of them having only spectre evidence against them and

their mittimusses being

defective, I caused some of them to be lettout upon bayle and put the

Judges upon consideration of a way to reliefe others and to prevent

them from perishing in prision, upon which some of them were

convinced and acknowledged that their former proceedings were too

violent and not grounded upon a right foundation ... The stop

put to the first method of proceedings hath dissipated the blak cloud

that threatened this Province with destruccion.” Governor William

Phips,

February 21st, 1693

Of

course, it is hard to put ourselves in the 1692 mindset of those who

actually believed in witch-craft and to whom the devil was a real

entity. Still, how could the accusers – many of them children –

be given such credence? This is not just hindsight; many argued at the time that there was no

basis to believe that their testimony was true – it made more sense

to believe that it was “made up.” But it was accepted by the

infamous Court, and people were executed on that basis.

There

was also a huge 17th Century Catch-22. If you confessed to

being a witch, you would be spared, but if you didn't you'd be

executed. Only those who were most true to their religion, refusing

to lie and steadfastly maintaining their innocence, were condemned

and executed. That in itself would seem to be a red flag that the

process was seriously flawed. Who couldn't see that? Why wasn't it obvious. Religious

zealotry can blind people to reason.

If anything good could come of such a travesty, the

Salem Witch Trials have served for centuries as a cautionary tale

against intolerance and mass hysteria. Apt parallels were

made during the McCarthy era, when the anti-communist fervor led to a

similar suspension of people's rights and lives were ruined based on

hearsay and associations. Arthur

Miller's play “The Crucible” was inspired by this very parallel.

The

Salem Witch Trials set a clear example of why the separation of

church and state is necessary. I would take it a step farther:

arguably, all religion is “spectral” - there is nothing tangible

that proves the tenets of the world's religions. They are based

on faith, not evidence. People's faith is real, but in any religion,

because the articles of faith are subject to people's

interpretations, there will always be differences of opinion and

interpretation about what they mean, or what is most important.

That's the nature of the beast.

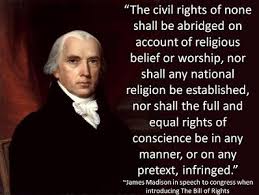

Many

of the founders recognized the evils that men do in the name of

religion. Practically speaking, they also had to blend the interests

of many people of different faiths, and some of no faith, to create a

viable political union. That included Rhode Island, founded on

principles of religious liberty and separation of church and state.

It included Dutch Mennonites in New York, German Lutherans in

Pennsylvania, Catholics, Jews, Episcopalians, Baptists, deists and,

yes, atheists. In fact, a number of key revolutionaries and founders

of the nation were deists, including George Washington, James

Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine and Ethan

Allen. They wisely built a wall to separate church and state.

We've

already had a theocratic tragedy in our early history which can serve

as a cautionary tale, if only we are willing to take heed: though

religion is supposed to be a force for good, mixing it with political

control is unwise and can lead to persecution and bloodshed.

More

than once it has been said…that the Salem witchcraft was the rock

on which the theocracy shattered.

— George

Lincoln Burr

Yet

some don't understand the history or choose not to heed the lesson.

The Dominionists are the Puritans of today, but with a much more

extreme political agenda, fewer scruples, and a stronger

determination to combine their religious beliefs with government.

Their 7 Mountains strategy

aims to take control of business, government, media, arts and

entertainment, education, family and religion. Here's a site that has

a lot of information on this topic. Their infiltration of all these areas is well underway; perhaps the

infiltration of not only the civilian government, but of the U.S.military, is particularly troubling.

We can

learn from history, or we can repeat it.