The court’s majority conservatives agreed that corporations have broad First Amendment rights and that “recent precedents upholding limits on corporate political spending should be overruled.” However, Sotomayor disagreed, and said the court should reconsider the 19th century rulings that first afforded corporations the same rights as real, live people.

Judges “created corporations as persons, gave birth to corporations as persons,” she said. “There could be an argument made that that was the court’s error to start with…[imbuing] a creature of state law with human characteristics.” [emphasis mine]

Corporations, Roscoe Conkling and the Fourteenth Amendment

Testifying in behalf of the railroads was the one of the most powerful politicians of his time for the most powerful state in the Union, Roscoe Conkling. His name may not mean too much today but in his time, Conkling was a man whose name carried weight. I compiled this information from his biography:

Testifying in behalf of the railroads was the one of the most powerful politicians of his time for the most powerful state in the Union, Roscoe Conkling. His name may not mean too much today but in his time, Conkling was a man whose name carried weight. I compiled this information from his biography:Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Their lawyers came up with the idea that corporations, which might be said to be groups of persons (though one person might in turn belong to (own stock in) many corporations), should have the same constitutional rights as persons themselves. If they could get the courts to agree that corporations were persons, they could assert that the States, which had chartered the corporations, would then be constrained by the 14th Amendment from exercising power over the corporations.Beginning in the 1870's corporate lawyers began asserting that corporations were persons with many of the rights of natural persons. It should be understood that the term "artificial person" was already in long use, with no mistake that corporations were claiming to have the rights of natural persons. "Artificial person" was used because there were certain resemblances, in law, between a natural person and corporations. Both could be parties in a lawsuit; both could be taxed; both could be constrained by law. In fact the corporations had been called artificial persons by courts in England as early as the 16th century because lawyers for the corporations had asserted they could not be convicted under the English laws of the time because the laws were worded "No person shall..."

The need to be freed from legislative and judicial constraints, combined with the use of the word "person" in the U.S. Constitution and the concept of the "artificial person," led to the argument that these "artificial persons" were "persons" with an inconsequential "artificial" adjective appended. If it could be made so, if the courts would accept that corporations were among the "persons" talked about by the U.S. Constitution, then the corporations would gain considerably more leverage against legal restraint.

These arguments were made by corporate lawyers at the State level, in court after court, and many judges, being former corporate attorneys and usually at least moderately wealthy themselves, were sympathetic to any argument that would strengthen corporations. There was a national campaign to get the legal establishment to accept that corporations were persons. This culminated in the Santa Clara decision of 1886, which has been used as the precedent for all rulings about corporate personhood since then.

The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does.

As Thom Hartmann uncovered in his book, Unequal Protection: The Rise of corporate Dominance and Theft of Human Rights, the task of giving a summary of the decision for the headnotes for the case fell to a man named John Chandler Bancroft Davis. He was no doubt confused about one fine point that had to be included in the headnote.

As Thom Hartmann uncovered in his book, Unequal Protection: The Rise of corporate Dominance and Theft of Human Rights, the task of giving a summary of the decision for the headnotes for the case fell to a man named John Chandler Bancroft Davis. He was no doubt confused about one fine point that had to be included in the headnote. As Wikipedia informs us:

Preceding every case entry is a headnote, a short summary in which a court reporter summarizes the opinion as well as outlining the main facts and arguments. For example, in United States v. Detroit Timber Lumber Company (1906), headnotes are defined as "not the work of the Court, but are simply the work of the Reporter, giving his understanding of the decision, prepared for the convenience of the profession.

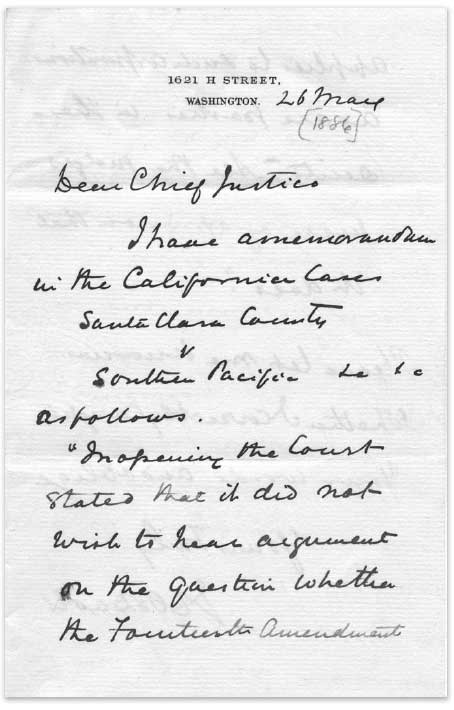

Bancroft Davis asked the Chief justice for clarification from the leader of the court,

Bancroft Davis asked the Chief justice for clarification from the leader of the court, "Please let me know whether I correctly caught your words and oblige."

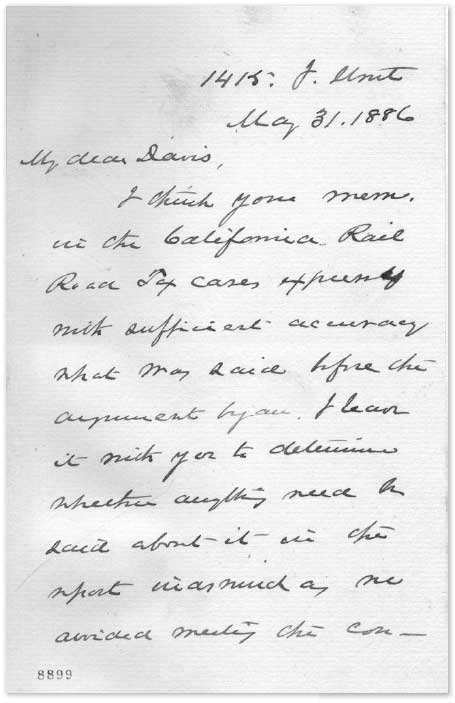

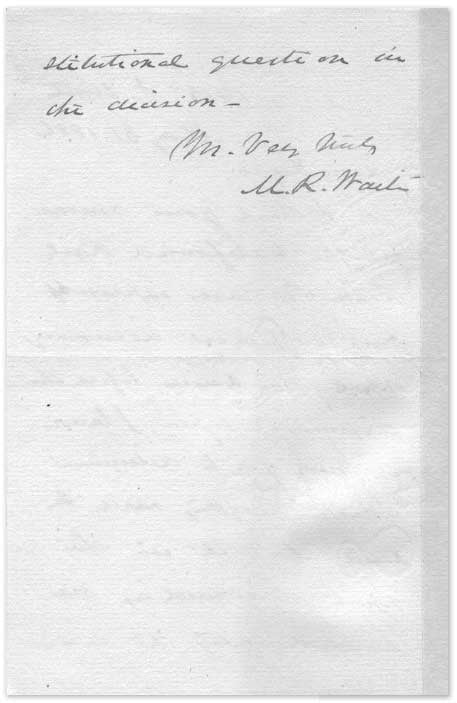

"I think your mem. in the California Rail Road tax cases expresses with sufficient accuracy what was said before the arguments began. I leave it with you to determine whether anything need be said about it in the report inasmuch as we avoided meeting the Constitutional question in the decision."[emphasis mine]

Thus the matter of corporate personhood left up to the discretion of a minor court reporter writing a summary headnote for a rather unremarkable case.

Thus the matter of corporate personhood left up to the discretion of a minor court reporter writing a summary headnote for a rather unremarkable case. That the provisions of the constitution and laws of California, in respect to the assessment for taxation of the property of railway corporations operating railroads in more than one county, are in violation of the fourteenth amendment of the constitution, in so far as they require the assessment of their property at its full money value, without making deduction, as in the case of railroads operated in one county, and of other corporations, and of natural persons, for the value of the mortgages covering the property assessed; thus imposing upon the defendant unequal burdens, and to that extent denying to it the equal protection of the laws. [emphasis mine]

In fact, as Graham pointed out, John A. Bingham, principle framer, employed these guarantees specifically and in a context which suggested that free Negroes and mulattoes (rather than corporations and business enterprise) unquestionably were the persons' to which he then referred. Whatever the lawyers for the railroad companies might have argued, there is no evidence to support their views.

Still, it’s worth a closer look. The same people who demanded the harshest possible terms for the South, The Radical Republicans, were in control of the Commission that drafted the amendment. This faction, at least by the records available to us, seem to have been motivated by the highest ideals of abolishing slavery. Thaddeus Stevens, leader of the faction, had defended and supported cases involving various minorities, Native Americans, blacks and women. His out-spoken stand against slavery was well-known to all who knew him. His desire for the emancipation of the slaves, the desire to abolish slavery as a institution in the United Sates was genuine. The history of this movement began some thirty years before as ethical, moral and religious argument.

There is not enough evidence to indicate a conspiracy among the drafters of the amendment, as far as I can detect.

Not every Supreme Court Justice was so easily convinced that corporation deserves to be considered “persons,” with constitutional citizen rights. For example, Justice Hugo Black, former Alabama senator turned Supreme Court Judge did not mince words about his feelings on this interpretation of the Constitution.

I do not believe the word 'person' in the Fourteenth Amendment includes corporations... This Court has many times changed its interpretations of the Constitution when the conclusion was reached that an improper construction had been adopted...When a statute is declared by this Court to be unconstitutional, the decision until reversed stands as a barrier against the adoption of similar legislation. A constitutional interpretation that is wrong should not stand. I believe this Court should now overrule previous decisions which interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to include corporations.Neither the history nor the language of the Fourteenth Amendment justifies the belief that corporations are included within its protection....Certainly, when the Fourteenth Amendment was submitted for approval, the people were not told that the states of the South were to be denied their normal relationship with the Federal Government unless they ratified an amendment granting new and revolutionary rights to corporations.

For example, as author, William Meyers points out,

Corporate personhood is at the root of such Supreme Court rulings as First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti [435 U.S. 765 (1978)], which equate corporate donations to political campaigns with free speech. They allow corporate money to govern the political process. These rulings can be reversed once the 1886 decision is reversed, since they are directly dependent upon it. Then we should be able to force corporations out of the political process. We could do this through legislation or through the chartering process. Without personhood the corporations are not entitled to First Amendment rights; they will have only what privileges the people, through our government, give them.

We can and should prohibit them from making any kind of contribution to politicians, to lobbying groups, or to campaigns involving referenda. Any advertising that does not sell products — that is, any advertising not presenting factual information about the products or services a corporation offers — should be prohibited.

Addition information can be found (full text) at The Santa Clara Blues: Corporate Personhood versus Democracy, by William Meyers.